|

Exerpt from an art show pamphlet

Listing of Credentials

Critique by Eve Medoff

Associate in Art Research, Hudson River Museum

Arts Editor, Yonkers Record

Critique by Gordon Brown

Senior Editor, ARTS Magazine

Exerpt from an unknown news article

News article by Lee Sheridan (1971?)

News article by Florence Berkman (1984)

Another exerpt from an unknown source

News article by Mike May (1985)

|

|

Exerpt from an art show pamphlet

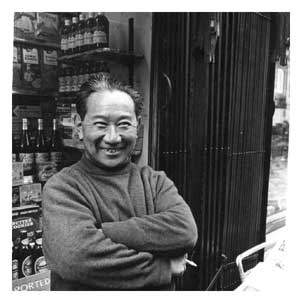

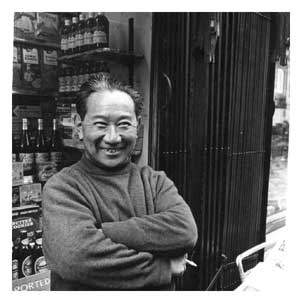

TSENG-YING PANG, one of the great artists in all of

the Orient’s long history, has defied Rudyard Kipling’s

conviction that "East is East and West is West and never

the twain shall meet."

The twain do meet - in Pang’s celebrated watercolors,

which art experts throughout the world have described as

an "occidental symphony with oriental indirection," and

with similar encomiums.

Born to a Chinese artist-mother in Japan, Pang at an early

age exhibited talents usually displayed by adults. His art

education is at roots Chinese. His initial studies were in

Peking, China, where beginning in his youth he studied the

various forms of Chinese art. After graduating from

Chunghua College of Art, Peking, Pang was awarded a

scholarship to Study art at Nippon University in Tokyo,

Japan. There he received his M.A. degree in art. His

amazing visionary powers, greatly influenced by the

traditional Asiatic art and Western techniques soon

established him as one of the Orient’s most esteemed

contemporary watercolorists.

Gordon Brown, Senior Editor of ARTS magazine, whose

enthusiasm for Pang’s work is unrestrained, wrote that

"Pang brings his own version of Abstract Expressionism. His

|

mood is predominantly poetic and leads to philosophical

meditation, It expresses grace, strength, elegance,

abruptness, and freshness as the occasion may require.

Through these qualities, that all nations can admire and

understand, he has made a splendid contribution toward the

internationalization of art while retaining rich values

that are national and personal."

In 1965 Pang was awarded Taiwan’s coveted President’s

Award and came to the United States on a grant from the

Asia Foundation. He has remained in this country and has

received more than 200 awards for his watercolor paintings,

many of which have become the proud possessions of

museums, galleries and private collectors throughout the

world.

|

|

CREDENTIALS:

NEW YORK TIMES:

"He has seized upon some aspect of a scene with genuine

visionary power"

(12-10-54)

HERALD TRIBUNE:

"He has several trends of style, showing free brush work

in some, flickering color or an almost Van Gogh-like turn

in others and a formal somewhat abstract style in still

other canvases. In all of them, he is a competent

technician, direct in painting and tasteful in color...

His work is influenced clearly by Western ideas."

(12.25.54)

ART DIGEST:

"Their tenor is generally solemn and moody, especially

in the landscapes, where broad and heavy rhythms and

dramatic dark colors evok, expressionist overtones...

There are occasional surprises, for at times Pang’s

palette moves from somber browns and dull greens to an

almost fauve brightness, and his simple weighty form can

change, as in Trees in Twilight, to on animated dance of

fiery trees against the blue night sky." - (1-55)

|

NEW JERSEY MUSIC AND MW’S:

"With each viewing of the watercolors of Pang Tseng-Ying,

one is readily carried into the mystique of Asiatic art at

the same time made aware of the ambivalence of his

expression. In tonal nuance and harmonious blending of

colors. Pang paints an Occidental symphony with Oriental

indirection."

ARTS MAGAZINE:

"Pang Tsing-Ying paints the countryside which poets write

about. Working on carefully prepared rice paper his

calligraphic strokes sing of rich ancestral heritage.

Although born in Tokyo, Pang is unmistakably a Chinese

artist. The abstract shapes, amorphous at first glance,

soon assume precise pattern and reveal a personal vision of

super-realism. A complexity of floating forms, rendered in

muted colors, tell brief stories of misty slopes and

budding trees. While it is true that this painter began his

artistic wanderings under Western influence as a kind of

Pascin-Iike portraitist, he has found his true style in

lauding his native soil. Pang’s forte is landscape. It is

Pang’s ethnical vision and sensitivity that recall Li

Ssu-Hsun’s formidable country scenes." (2-68)

|

|

AMERICAN ARTISTS:

"The wealth of imagery in Chinese painting through the

centuries offers on inexhaustible resource to the artist.

In his art, Tseng-Ying has distilled from that treasure the

elements his own needs dictate: the expressive stroke, the

flowing, rhythmical movement, the lyrical quality." (9-68)

|

|

|

Tseng-Ying’s maturation as an artist coincided with the

realization that ‘western style’ painting fitted him

uncomfortably like a suit sewn for someone else. To find

his own pattern, it was necessary to travel backwards in

time to the art of his ancestors and look to the present.

This introspective journey led to a vantage point where

cultural memory served the 20th century man in his search

for identity. Now Pang was ready to face the difficult task

of learning to let his hand do what his heart dictated.

What finally emerged on the rice paper which replaced the

less felicitous canvas were exultant, bounding staccato

images which leap off the brush as readily as the

calligraphic strokes taught him in childhood by his artist-

mother. Calligraphy is also seen in the delicate traceries

woven in and out of sweeping color galaxies. Pang prepares

the paper he uses with meticulous care to enable it to

receive the colors applied again and again until the

emotional demands of the painting are satisfied. Deep,

muted colors have the rich complexities of embroidered

silks in some pictures; in others, the spacial quality of

Chinese landscapes painted on scrolls is felt in the

floating, weightless forms.

Pang has found his aesthetic vocabulary in an East-West

equation: his ancestral heritage on the one hand; on the

other the indomitable urge to express the immediacy of the

moment. Armed with this equation, he began, cautiously at

|

first and in total absorption, to communicate his vision.

Recent paintings, however, indicate that the pace is

quickening. In the current scene, he moves surely and with

grace.

What the New York Times called Pang’s "genuine visionary

power" has begun to flex its muscles. For many collectors,

Pang-watching is bound to become a fascinating pursuit.

EVE MEDOFF

Associate in Art Research,

Hudson River Museum;

Arts Editor, Yonkers Record

|

|

TSENG

YING

PANG

A venerable Chinese sage is depicted on the left side of

Tseng-Ying Pang’s painting, "Dramatic Grouping" (1967).

This wise man may well he the artist’s Guiding Spirit, for

Pang, after a thorough study of western methods. Visible in

his early work, he has returned, at least in part, to the

style of his ancestors. He has so ably subordinated western

influences to eastern moods that one can only regard his

present manner as oriental. Eastern elements in Pang’s

inspired paintings include the free composition, the

reliance on tone rather than color to establish the basic

forms and the use of blank spaces as essential parts of the

design. His pictures vary in their degree of reliance on

western concepts. "Flowers and Cold Rock" (1967) offers

meticulous factual draughtsmanship very western in spirit.

In fact, Pang, seemingly preoccupied with oriental feeling,

has actually advanced in his mastery of western technique.

Yet the East remains in the blank spaces where the viewer

uses his own imagination, to carry on the imagery and in

the misty, atmospheric sections which are poetically

evocative rather than scientifically descriptive. Pang’s

paintings come close to Abstract Expressionism which, on

its part, comes close to Pang. The work of Franz Kline, for

example, has been greatly influenced by oriental

calligraphy. There are other parallels between the work of

|

Pang and Abstract Expressionism.

He has abolished the fixed point of view of traditional

occidental perspective, encouraging the viewer’s eye to

move over the whole picture. His imagery is often subject

to change as the viewer creates his own configurations.

Pang brings his own personal qualities to his version of

Abstract Expressionism. His mood is predominantly poetic

and leads to philosophic meditation. He has a greater

variety of brushstrokes at his command than the average

western artist. Note the light delicacy of his snow scenes

and the powerful heavy spotting in his "Maelstrom." With

remarkable economy of means, Pang’s magic brush expresses

grace, strength, elegance, abruptness and freshness as the

occasion may require. These are qualities that all nations

can admire and understand. Pang has made a splendid

contribution toward the internationalization of art while

retaining rich values that are national and personal.

Gordon Brown,

Senior Editor. ARTS Magazine

|

|

Exerpt from unknown newspaper

Tseng-Ying Pang

The works of Chinese artist Tseng-Ying Pang, who came to

this country in 1966, will go on exhibit this afternoon for

the remainder of the month at the Columbus Museum of Arts

and Crafts. A reception will take place from 4-6 p.m.

marking the opening.

Mr. Pang is a very serious and sensitive painter and an

extremely meticulous worker. He prepares his own paper with

great care, a rumpled rice paper that will take the ink

washes and paint more effectively. Usually he does not

start a work with a definite subject in mind although it

would be rare that some aspect of nature was not envisioned

by his sub-conscious. He applies color again and again

until the emotional demands that are in his heart have been

satisfied. He often stops work on one painting and goes on

to another, sometimes having four or five paintings in

process at one time. He uses four layers of rice paper,

glued together with paste, and the texture of the paper

itself becomes an integral part of his painting.

|

|

|

SPRINGFIELD, MASS, DAILY NEWS

Chinese Watercolors

Mix Oriental, Western

By LEE SHERIDAN

The recently opened exhibit of Chinese watercolors by

Tseng-Ying Pang at the Holyoke Museum, Wistariahurst, had

its beginnings last May in New York City when Museum

Director Mrs. Marie S. Quirk first became acquainted with

the work of the artist at the annual meeting of the

American Association of Museums. "When I saw an exhibit of

Pang’s paintings at the Waldorf-Astoria I was quite

impressed," Mrs. Quirk said in a Daily News interview. She

added that she had met the artist at the museums

association meeting and made tentative plans with him,

which culminated in the present exhibit.

Mrs. Quirk considers the work of Pang particularly unique

since it brings Oriental feeling to western style

techniques and approaches. Describing the paintings as

"enchanting," the museum director said that the watercolors

on rice paper are "muted, subtle colors" and deal mostly

with nature — ledges, boulders, mountains, plant forms,

with "the suggestion of a little tree here and there."

Some paintings Mrs. Quirk said, are "ethereal," some

abstract but with delicate, calligraphic line tracery, some

"most unusual" in that they are peopled with tiny figures.

"It requires a bit of study to really see and appreciate

|

the great amount of detail," said Mrs. Quirk.

Although Pang was born in Tokyo he is of Chinese parents

and unmistakably a Chinese artist the museum director

explained, working in abstract shapes which, upon

contemplation, assume precise patterns and personal

realism.

Pang was privately educated in the traditional arts of

calligraphy and painting in Peiping and studied Western

painting at Chinghua Art College, where he graduated in

1937. After an assistant instructorship in art at the same

college he was awarded a scholarship for study in Japan.

Head of the art department of Hubsien College in Xian

from 1941-44, the artist then taught in Taiwan until he

came to the U. S. on a grant by the Asia Foundation in

1965.

Pang’s first one-man show in this country was in l954 at

the Argent Gallery in New York City, while he was still in

Taiwan. Since then he has had numerous New York City shows

as well as in Detroit and has participated in more than 50

art association shows in New York, New Jersey, and

Massachusetts, including the Berkshire Art Association.

Chinese watercolors by Tseng - Ying Pang will be on

exhibit at the Holyoke Museum through Feb. 20, Monday

through Saturday from 1 to 5 pm. and Sunday from 2 to 5 pm.

|

|

The Middletown (Conn.) Press,

Friday Evening! September 21, 1984

Art: Work by Tseng-Ying

By FLORENCE BERKMAN

Tseng-Ying Pang’s paintings prove wrong Rudyard Kipling’s

conviction that "East is East and West is West and ne’er

the twain shall meet."

A collection of his watercolors now on view at the New

England Center for Contemporary Art in Brooklyn, brings

together the basic techniques of Chinese art, its poetic

interpretations of nature and the freedom of 20th century

abstract-expressionism.

Recently an editor of ARTS Magazine wrote: "Pang brings

his own version of Abstract-Expressionism. His mood is

predominantly poetic and leads to philosophical meditation.

It expresses grace, strength, elegance, abruptness, and

freshness as the occasion may require. Through these

qualities, that all nations can understand and admire, he

has made a splendid contribution toward the

internationalization of art while retaining rich values

that are national and personal."

The interesting point about the effect of abstract-

expressionism on Pang’s art, is that the American abstract-

|

expressionists were strongly influenced by Chinese art. The

thing has come full circle in Pang’s work.

These are ingratiating works on view. They invite the

imagination to wander and there is a tranquility, a oneness

with nature that provides the viewer with a peace that has

been absent in American art indeed since the advent of

abstract-expressionism.

Strangely, there was no peace in the heart of this artist

when he created many of the works. I noticed he had placed

tiny human figures in the folds of color and form. In an

interview, I asked Pang what these meant. Putting his hand

over his heart, he explained that they represented the most

tragic period of his life: World War II, when Japan invaded

China and he and his family had to leave their homes and

wander in the mountains begging food and money to live.

Pang said he could not get that

period with its travails out of his mind. For a number of

years he painted scenes that recalled the days of wandering

for his family and for so many Chinese. Often the people

from whom they begged received them with kindness; other

times there was only cruelty.

|

|

Pang was born in [1916] to a Chinese artist in Japan, and

at an early age showed great talent. He returned to China,

however, to study the various forms of Chinese art.

After graduating from the College of Art in Peking, he

was awarded a scholarship to study art at Nippen University

in Tokyo where he received his master’s degree. Art

scholars there were impressed with his visionary powers

which were influenced by the traditional Asiatic art and

Western techniques. This soon established him as an

important contemporary watercolorist. Later he moved to

Taiwan, where, in 1965 he received the President Chiang

Kai-Shek Award and a grant from the Asia Foundation which

brought him to the U.S.

During the 1930s Pang became aware of Western art. "For

me Cezanne, Van Gogh and Gauguin were most inspirational,"

he said. Predominantly a landscapist, he brought both

cultures together in the complexity of floating forms,

abstract shapes, amorphous at first, which on closer

examination turn out to be "misty slopes and budding

trees."

For many years Pang emphasized the Western influence, he

said. "Now I am going back to my roots - the Oriental

approach to nature and to the world." Art critics have

marvelled at Pang’s "genuine visionary power" and predicted

that "for many collectors Pang-watching is bound to become

|

a fascinating pursuit." Since his arrival in America he has

had over fifty exhibitions - one-man shows and in group

shows and has been the recipient of many awards. Viewing an

exhibition in the openness of the countryside at the New

England Center for Contemporary Art adds a pleasurable note

to the occasion. Located on Route 169 it is about 50 miles

from central Connecticut.

Admission is free, hours are daily and Sunday from 1 to

5 p.m.

|

|

Exerpt from Unknown Newpaper

In the world of saavy art collectors, Tsen-Ying Pang

needs very little introduction. Like a movie star, Pang has

fans who watch his works carefully - always searching for a

unique piece that will please them visually and appreciate

in value.

Pang specializes in watercolors and his work has been

hailed by art experts throughout the world as an

"occidental symphony with oriental indirection." His new

collection now is being shown at the Hartley Gallery on

Park Avenue in Winter Park.

In addition to painting living creatures, flowers and

other objects either in abstract or realism, he always

manages to induce subtle moods in viewers. He says he is

fascinated and obsessed with the colors and imagery he sees

in his dreams and tries to transform them onto his

paintings.

One of his latest works "Raindrops" is an example,

infused with bluish gray and lightest pink colors, and

dotted with imperfect circles of soft cloud like color.

He said he paints from early morning to the wee hours of

the night, taking hardly any time out, even for a chat with

his wife. "That’s why I can’t speak or explain my paintings

|

in English too well," said the Taiwanese born artist. "When

I sleep, all I can think of is my painting, trying to

figure out how to draw certain objects and what color I

want. I beat my brains out and dream about it," he said

laughing.

|

|

Kiss Kiss, Pang Pang

by Mike May

"East is East and West is West and...

a) ...never the twain shall meet."

b) ...the wrong one I have chose."

c) ...now you can start your morning with Egg McMuffin

wherever you happen to be."

d) ...the twain do meet in Pang’s celebrated

watercolors."

Choose "d" and you have a description of Tseng-Ying Pang

as given by Bondstreet Gallery’s John Gillespie. (FYI: "a"

is from Rudyard Kipling; "b" is the old song "Buttons and

Bows," a Doris Day staple; and "c." well, if you have to

ask, you should be writing memoirs about what it’s like to

leave a larnasery after three decades.

Bondstreet, at 5640 Walnut Street, Shadyside, has a

retrospective exhibit of watercolors and serigraphs by

Pang, commemorating his 22 years of residence in the United

States.

It’s a beautiful show, and Gillespie has played up the

mood of the mysterious East in the gallery with such

Orientalia as cloisonne figurines, highly carved blackwood

furniture, and Occidental ideas of Oriental music as

background sound—"The 101 Strings Live at Peking’s

|

Forbidden City." or something like that. (And John

Gillespie says one "art expert" described Pang’s work with

musical imagery. He sees it as "an Occidental symphony with

Oriental indirection.")

It’s certainly lyrical, all right. And romantic, but with

control and understatement.

After receiving the Republic of China’s (Taiwan’s)

coveted President’s Award in 1965, Tseng-Ying Pang came to

America on a grant from the Asia Foundation. Since his

arrival, he has received more than 200 awards here for his

watercolors. Pang was graduated from Chunghua College of

Art in Peking, and later received a scholarship to study

art at Nippon University, in Japan, his birthplace. His

mother was a Chinese artist residing there.

Although his artistic roots are Chinese, the influence of

the Occident is apparent in his work. One need only note

such obviously titled watercolors as "Homage to Miro (I and

II)."

Gordon Brown, former senior editor of Arts magazine,

described Pang’s art as "his own version of abstract

|

|

expressionism." However, Pang never really strays over the

borders into true abstract expressionism. except in pieces

like the Miro homages. And these are not his best work.

Actually, they look like Rorschach blots.

No, it’s the romantic Orientalisms gently ruffled with a

touch of the West wind that makes his art captivating. His

enchanting mountains, whispers, mists, flowers, leaves and

autumn breezes—described with an elegant sensuality of

color never stray far from reality. Or perhaps, what

reality should ideally be.

His look at goldfish in several serigraphs and paintings-

"Goldfish Ballet," "Golden Pond"-gives a glimpse at the

creatures as though studied through the glass surface of

still, ever-clear water. They seem to float effortlessly,

timelessly.

In the end, it’s the timeless quality of Pang’s art

that’s impressive. His vision has that kind of universal

appeal-big enough to encompass yesterday, today and

tomorrow.

There’s promise that someone, somewhere will always

understand that vision. And long after Egg McMuffin is a

dusty footnote on the relentless march of time.

|

|

|